I came to the big city. I had a job. My father got it for me, and I was just married. You might say that I had my husband to comfort me and stuff, but in truth, he really didn’t. He was away, and then he came back, then he went away, then he went to India, which he loved. I probably would have loved it too, but I didn’t have the option. So anyway, I got married, and I left for my honeymoon as it were, and I could see that my father, who was sort of seeing me off, was terribly worried, but I didn’t realize that Peattie hadn’t made any provision for me really. He got me the key to this apartment, which it so happened that there was probably some difficulty about that too.

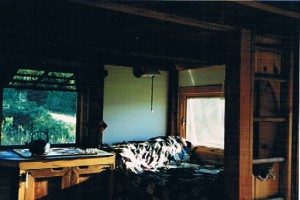

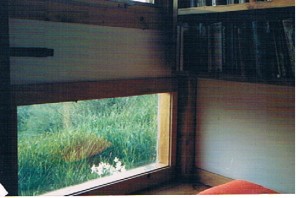

All this time we were living in this odd arrangement where we had the use of an apartment that didn’t have much in it, and I used to get up every day and climb down a ladder to get the breakfast. Anyway, there we were

I took the coach [train] down to Washington. It was pretty jumbly because it was wartime [WWII]. I slept curled up on a folding table, a card table, in the coach, and the guy on the next table was stroking my ankle the whole way. That was quite pleasing. It was just one of the peculiarities of train travel in those days. Those were the days it was.

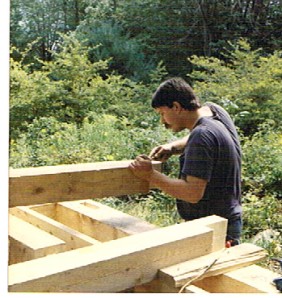

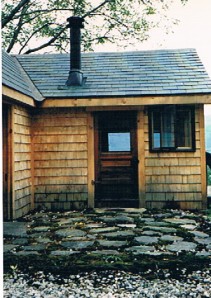

So I got to this apartment, and I had a key! I don’t remember how I got the key, if Peattie had mailed it to me or what, but in some manner he had gotten me the key and so I let myself in, and there I was. And it was an actual apartment. We’d been living in the peculiar way in Cabin John.

But it wasn’t even an anonymous apartment. It was the apartment, actually, of this couple Peattie knew who worked at the Map Service. They had gone off, they’d departed. That was a whole set of complications. There were no apartments because of the war. Nobody could get anything. It was absolutely a triumph to have an apartment. Although it didn’t trickle down too well, I had the apartment, I had the key.

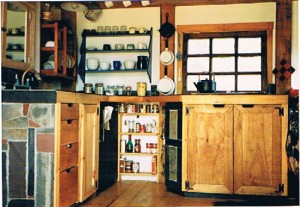

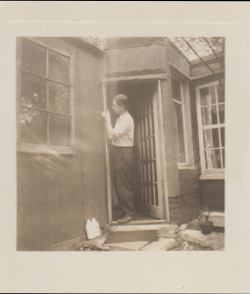

Peattie had been getting ready to paint the apartment, but he didn’t get so far as to paint it. He enrolled in this thing [AFS] and he was gone off, and I had the apartment, which I must say was quite pleasing after the peculiarities of life in Cabin John, and it turned out that Peattie had left a gallon of paint, and he had pulled everything out of the kitchen to be ready to paint, but that was as far as he’d gone.

It was the saddest I’d ever been. I was terribly lonesome. I wanted somebody to greet me, to give me a big hug. If I had known anybody at all, I would certainly have rung them up and said “Let’s go have coffee” but I didn’t. So I just stood there for a while sort of with my finger in my mouth, and then I pulled myself together and got ready to paint, and I guess I began painting.

I was like a newborn babe. I didn’t have ambitions, I didn’t have plans, I didn’t have experiences you could replicate…. I was just a beginning person.

It was a moment of growing up. It was just me, and there wasn’t going to be anybody else. I wasn’t mad at Peattie, either. I just felt like there wasn’t anybody in the world I could reach out to, and there wasn’t.